if these walls could listen

if these walls could listen

To use a well-known phrase, "Cairo writes, Beirut prints, and Baghdad reads," similarly reflects the story of radio in the region.

To use a well-known phrase, "Cairo writes, Beirut prints, and Baghdad reads," similarly reflects the story of radio in the region.

By Hazem Madbouly

By Hazem Madbouly

10 minutes read - Published 09.09.2024

10 minutes read - Published 9.9.2024

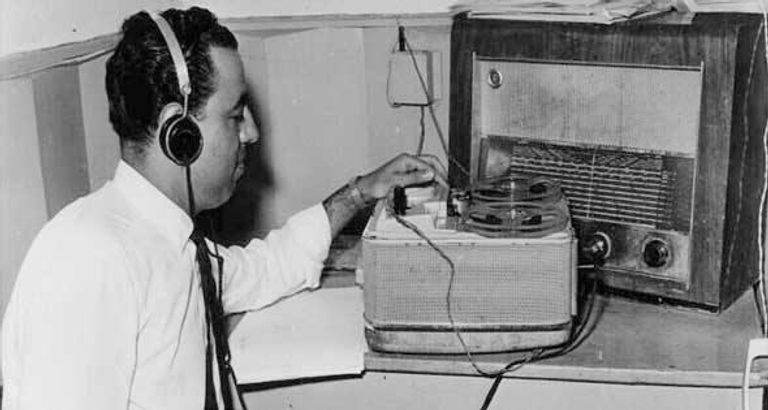

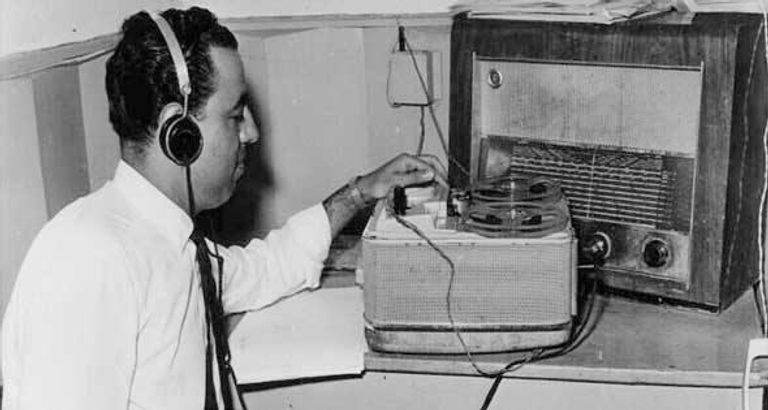

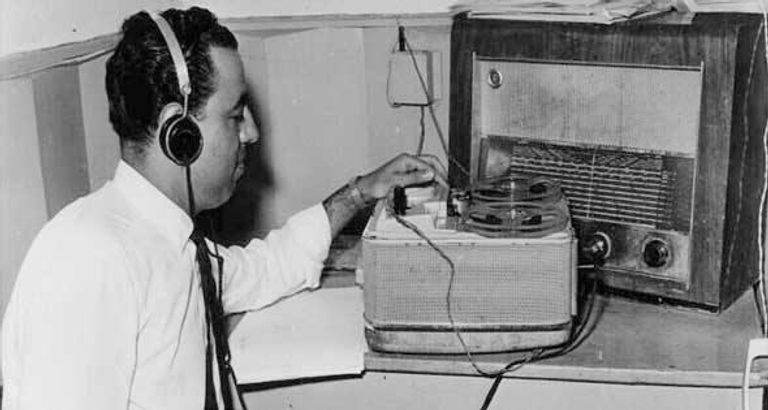

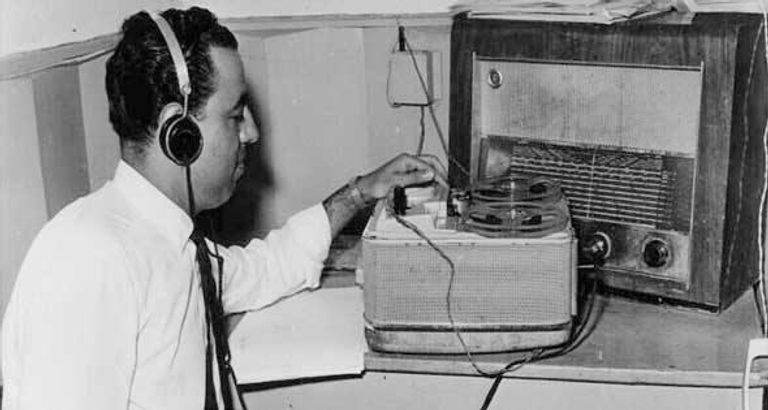

On July 1, 1934, at approximately 5 p.m., Egyptians tuned in to the Cairo Egyptian Radio Station to hear Ahmed Salem utter what would become one of the country’s most iconic phrases, "Huna Al Qahera" ("This is Cairo").

Whether intentional or not, broadcasting in North Africa and the Arab world paralleled the shifting political, social, and cultural transformations in society. To use a well-known phrase, "Cairo writes, Beirut prints, and Baghdad reads," similarly reflects the story of radio in the region. In 1934, Radio Liban—known at the time as Radio Orient — began broadcasting, and a few years later, in 1936, Radio Baghdad took third place in the race to live broadcasting.

That same year, in Palestine, then under British mandate, the Palestinian Broadcasting Service (PBS) was founded. Its inception was framed as the British government’s commitment to supporting Palestine's trajectory toward independence. The station featured music, news, and entertainment programming, but it had a tumultuous start, to say the least. Just one month in, the Great Palestinian Rebellion began, prompting the British to quickly increase their oversight of the news content. Although prominent figures like Ajaj Nuwayhed and Azmi al-Nashashibi made persistent efforts to forge a way forward with specially tailored programming for Arabic-speaking Palestinians, the station did not survive and ceased broadcasting in 1948.

On July 1, 1934, at approximately 5 p.m., Egyptians tuned in to the Cairo Egyptian Radio Station to hear Ahmed Salem utter what would become one of the country’s most iconic phrases, "Huna Al Qahera" ("This is Cairo").

Whether intentional or not, broadcasting in North Africa and the Arab world paralleled the shifting political, social, and cultural transformations in society. To use a well-known phrase, "Cairo writes, Beirut prints, and Baghdad reads," similarly reflects the story of radio in the region. In 1934, Radio Liban—known at the time as Radio Orient — began broadcasting, and a few years later, in 1936, Radio Baghdad took third place in the race to live broadcasting.

That same year, in Palestine, then under British mandate, the Palestinian Broadcasting Service (PBS) was founded. Its inception was framed as the British government’s commitment to supporting Palestine's trajectory toward independence. The station featured music, news, and entertainment programming, but it had a tumultuous start, to say the least. Just one month in, the Great Palestinian Rebellion began, prompting the British to quickly increase their oversight of the news content. Although prominent figures like Ajaj Nuwayhed and Azmi al-Nashashibi made persistent efforts to forge a way forward with specially tailored programming for Arabic-speaking Palestinians, the station did not survive and ceased broadcasting in 1948.

0:00/1:34

0:00/1:34

0:00/1:34

Lebanon’s broadcasting was bilingual, airing in both Arabic And French. It was Radio Liban that first introduced the country to the voice of Fairouz, known as the "Bird of theEast."

In the years that followed, Radio Cairo launched what would become the most consequential radio program in the Arab world, “Sawt El Arab” or “Voice of the Arabs.” Through this program, Egypt, in no subtle terms, promoted anti-colonial rebellion in North Africa and the Arab world. It supported leaders in Morocco and Tunisia and aided Algerian revolutionaries against France.

In the years that followed, Radio Cairo launched what would become the most consequential radio program in the Arab world, “Sawt El Arab” or “Voice of the Arabs.” Through this program, Egypt, in no subtle terms, promoted anti-colonial rebellion in North Africa and the Arab world. It supported leaders in Morocco and Tunisia and aided Algerian revolutionaries against France.

0:00/1:34

Programming across all Arab radio services was state-controlled. In Egypt, broadcasts began with a Quranic recital, followed immediately by music from Umm Kulthum or Mohamed Abdel Wahab. In Iraq, the day started with a full minute of the whistling nightingale.

Programming across all Arab radio services was state-controlled. In Egypt, broadcasts began with a Quranic recital, followed immediately by music from Umm Kulthum or Mohamed Abdel Wahab. In Iraq, the day started with a full minute of the whistling nightingale.

Thereafter, Arab radio largely followed the same pattern: war reporting, entertainment shows, new musical sensations, and then back to war reporting. It’s safe to say that the rise of cinema and television coincided with the end of the golden age of radio. By that time, nothing captured the Arab world's attention more than turning on the TV, which became the primary gateway to the cultural and political pulse of the1980s and 1990s, offering an unprecedented sensory experience that resonated across the region.

Radio stations stayed within their silos. Egyptian radio remained culturally relevant and elevated its stature by hiring and training highly skilled presenters for Egypt’s European Program Radio, the country’s second oldest broadcast service, to compete with the best broadcasts globally. Radio Liban played an instrumental role in reporting the plight of Christian Arabs across North Africa and the Arab world. For example, consider this brief excerpt from a broadcast in the 1980s.

Thereafter, Arab radio largely followed the same pattern: war reporting, entertainment shows, new musical sensations, and then back to war reporting. It’s safe to say that the rise of cinema and television coincided with the end of the golden age of radio. By that time, nothing captured the Arab world's attention more than turning on the TV, which became the primary gateway to the cultural and political pulse of the1980s and 1990s, offering an unprecedented sensory experience that resonated across the region.

Radio stations stayed within their silos. Egyptian radio remained culturally relevant and elevated its stature by hiring and training highly skilled presenters for Egypt’s European Program Radio, the country’s second oldest broadcast service, to compete with the best broadcasts globally. Radio Liban played an instrumental role in reporting the plight of Christian Arabs across North Africa and the Arab world. For example, consider this brief excerpt from a broadcast in the 1980s.

In the early 2000s, with the rise of pop music, a few radio stations emerged and quickly reminded people of the joys of listening to the radio. Radio transitioned from being a primary form of home entertainment to becoming a staple in the car. Stations like Egypt’s Nogoom FM, Nile FM, Virgin Radio Lebanon, Tunisia’s Express FM, and others became the default soundtracks for commuters as they ran errands or rushed to work.

There is no denying that Radio in the Arab World is the most important story teller in its history. Although radio today is not what it was in the 40s or 50s and maybe even in the early 2000s, it still holds a very special place in the hearts of its listeners. It also resonates with me personally in its own way. I grew fond of audio in the past years because of the rise of podcasts, similar to the story of how radio’s inception, I too gravitated towards audio during times of personal reflections, yearning to connect in forms maybe different from reading a self help book or watching a documentary about the history of my culture. With the rise of podcasts, this new and innovative storytelling form of broadcasting, I found myself wondering what it would’ve been like to listen to Fairouz’s first recording on Radio Orient, or tuning in to Gamal Abdelnasser’s resignation speech following Egypt’s defeat in the 6 day war.

This pre-recorded 30 minute broadcast, now the most sought after communication vessel for anyone who once dreamed of being a radio presenter, managed to capture my attention and stir up feelings of nostalgia and belonging. Of all the podcasts out there and It is reported that as of this year, there are about 5 million podcasts worldwide, and those in the Arabic language are about 12 thousand, I tune in to Kerning Cultures. A podcast network telling stories in Arabic and English from the MENA and SWANA regions that, for me, evoked memories of growing up in Cairo listening to the radio with my dad in his car.

Listening to podcasts helped me find a new sense of appreciation for broadcasting which was conceived to help inform, entertain, mobilize, educate and instil a sense of belonging that only now, in reflection, stands true and revolutionary and beyond its time.

In the early 2000s, with the rise of pop music, a few radio stations emerged and quickly reminded people of the joys of listening to the radio. Radio transitioned from being a primary form of home entertainment to becoming a staple in the car. Stations like Egypt’s Nogoom FM, Nile FM, Virgin Radio Lebanon, Tunisia’s Express FM, and others became the default soundtracks for commuters as they ran errands or rushed to work.

There is no denying that Radio in the Arab World is the most important story teller in its history. Although radio today is not what it was in the 40s or 50s and maybe even in the early 2000s, it still holds a very special place in the hearts of its listeners. It also resonates with me personally in its own way. I grew fond of audio in the past years because of the rise of podcasts, similar to the story of how radio’s inception, I too gravitated towards audio during times of personal reflections, yearning to connect in forms maybe different from reading a self help book or watching a documentary about the history of my culture. With the rise of podcasts, this new and innovative storytelling form of broadcasting, I found myself wondering what it would’ve been like to listen to Fairouz’s first recording on Radio Orient, or tuning in to Gamal Abdelnasser’s resignation speech following Egypt’s defeat in the 6 day war.

This pre-recorded 30 minute broadcast, now the most sought after communication vessel for anyone who once dreamed of being a radio presenter, managed to capture my attention and stir up feelings of nostalgia and belonging. Of all the podcasts out there and It is reported that as of this year, there are about 5 million podcasts worldwide, and those in the Arabic language are about 12 thousand, I tune in to Kerning Cultures. A podcast network telling stories in Arabic and English from the MENA and SWANA regions that, for me, evoked memories of growing up in Cairo listening to the radio with my dad in his car.

Listening to podcasts helped me find a new sense of appreciation for broadcasting which was conceived to help inform, entertain, mobilize, educate and instil a sense of belonging that only now, in reflection, stands true and revolutionary and beyond its time.

It was a long war for Egypt, and much happened during that time, but most notably, the broadcast services suffered a significant loss of credibility. The Egyptian army used its programming to spread propaganda and misinformation about Egypt’s position in the war, announcing inflated numbers of enemy fighter jets shot down and soldiers killed. With the war's conclusion in 1967, Radio Cairo aired Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s speech announcing his resignation.

It was a long war for Egypt, and much happened during that time, but most notably, the broadcast services suffered a significant loss of credibility. The Egyptian army used its programming to spread propaganda and misinformation about Egypt’s position in the war, announcing inflated numbers of enemy fighter jets shot down and soldiers killed. With the war's conclusion in 1967, Radio Cairo aired Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s speech announcing his resignation.

The program criticized Iraq's participation in the Baghdad Pact and urged Jordanians to oppose it, contributing to the 1958 Iraqi Revolution. From 1956 to the 1960s, it incited anti-British actions in North Yemen, clashing with Saudi Arabia. It is not an overstatement to say that “Voice of the Arabs” was perhaps the Arab nation’s most successful attempt at unity. During the 1956 offensive against Egypt by Israel, the United States, and the United Kingdom, in pursuit of the Suez Canal, Radio Cairo was either caught or deliberately targeted by missiles and went off the air. Broadcasts from Iraq, Tunisia, and Syria then decided to each start their programming with one sentence: “This is Voice of the Arabs, from Radio Cairo, Egypt.

The program criticized Iraq's participation in the Baghdad Pact and urged Jordanians to oppose it, contributing to the 1958 Iraqi Revolution. From 1956 to the 1960s, it incited anti-British actions in North Yemen, clashing with Saudi Arabia. It is not an overstatement to say that “Voice of the Arabs” was perhaps the Arab nation’s most successful attempt at unity. During the 1956 offensive against Egypt by Israel, the United States, and the United Kingdom, in pursuit of the Suez Canal, Radio Cairo was either caught or deliberately targeted by missiles and went off the air. Broadcasts from Iraq, Tunisia, and Syria then decided to each start their programming with one sentence: “This is Voice of the Arabs, from Radio Cairo, Egypt.

In 1948, broadcasts across the Arab world were pivotal in informing the public about the war in Palestine. Interviews with soldiers were regularly conducted, and the army used radio to update the families of those deployed, using the soldiers' own voices in an effort to boost morale.

Soon after, Egyptian radio became the most influential political vessel in the country, and some would argue, in North Africa and the Arab world. It was Egyptian radio that, in 1952, announced the ousting of King Farouk when the Free Officers took over the broadcasting services, leading the coup.

Although the artists who entertained under the monarchy were the same ones who praised the military during the coup, entertainment programming during the 1950s on Radio Cairo expanded to include folk singers who better reflected the voices of the Egyptian streets. This period, known as the golden age of Egyptian radio, marked the beginning of serial audio sitcoms like “An Hour for Your Heart,” “Two Words Only,” “Try Your Luck,” and “City Lights.” These programs captivated listeners, and their stars quickly became recognized as pioneers in Egypt’s arts scene.

In 1948, broadcasts across the Arab world were pivotal in informing the public about the war in Palestine. Interviews with soldiers were regularly conducted, and the army used radio to update the families of those deployed, using the soldiers' own voices in an effort to boost morale.

Soon after, Egyptian radio became the most influential political vessel in the country, and some would argue, in North Africa and the Arab world. It was Egyptian radio that, in 1952, announced the ousting of King Farouk when the Free Officers took over the broadcasting services, leading the coup.

Although the artists who entertained under the monarchy were the same ones who praised the military during the coup, entertainment programming during the 1950s on Radio Cairo expanded to include folk singers who better reflected the voices of the Egyptian streets. This period, known as the golden age of Egyptian radio, marked the beginning of serial audio sitcoms like “An Hour for Your Heart,” “Two Words Only,” “Try Your Luck,” and “City Lights.” These programs captivated listeners, and their stars quickly became recognized as pioneers in Egypt’s arts scene.

In 1948, broadcasts across the Arab world were pivotal in informing the public about the war in Palestine. Interviews with soldiers were regularly conducted, and the army used radio to update the families of those deployed, using the soldiers' own voices in an effort to boost morale.

Soon after, Egyptian radio became the most influential political vessel in the country, and some would argue, in North Africa and the Arab world. It was Egyptian radio that, in 1952, announced the ousting of King Farouk when the Free Officers took over the broadcasting services, leading the coup.

Although the artists who entertained under the monarchy were the same ones who praised the military during the coup, entertainment programming during the 1950s on Radio Cairo expanded to include folk singers who better reflected the voices of the Egyptian streets. This period, known as the golden age of Egyptian radio, marked the beginning of serial audio sitcoms like “An Hour for Your Heart,” “Two Words Only,” “Try Your Luck,” and “City Lights.” These programs captivated listeners, and their stars quickly became recognized as pioneers in Egypt’s arts scene.

Lebanon’s broadcasting was bilingual, airing in both Arabic And French. It was Radio Liban that first introduced the country to the voice of Fairouz, known as the "Bird of theEast."

0:00/1:34

0:00/1:34

0:00/1:34

0:00/1:34

0:00/1:34

0:00/1:34